"Art was not separate from everyday experience."

The face jug is a staple motif in southern folk pottery, portraying the humorous "aesthetic of the ugly."

I spent over two hours of pure joy and pleasure this weekend drinking in an exhibit that told its story with folk art: hand crafted chairs, cotton-picking plows and tools, buttons made of sea mussels, the most enormous mortar and pestle I've ever seen, Victorian- and African-inspired quilt motifs. I can't remember the last time I left a museum in such a giddy rush. I went to the Atlanta History Center for the sole purpose of visiting their many exhibits--for the first time in my life. This is really sad, considering I have a degree in history, I'm earning a master's student studying museums, and I've lived in Atlanta for more than five years. In my defense, I've been there once to see one specific exhibit, and we also got a tour of the innards of the place, including their giant holdings areas down below where they keep the collection pieces that are not on display in exhibits. I have also been to their Kenan Research Center on several occasions for research purposes. But this was my first time going to meander my way through their permanent and temporary exhibitions.

Folk art meets daily life necessity: rice hulling mortar and pestels, circa 1800s (used into the 1900s). This is the most enormous mortar and pestel I've ever seen.

I knew I needed to pick one to highlight for yet another assigned exhibit review for a class (this makes about the fifth review I've done), but I didn't really go in thinking of any one in particular--especially not, for some reason, the folk art exhibit, which I'd heard one or a few classmates discuss before but never given much thought. But this semester, I'm taking a class on Material Culture, on the things we adorn with a human touch, and make with a purpose, be it necessity, pleasure, tool, comfort or any other reason we have to create something. In the wake of this summer's interior design class, I already feel that I am more aware of the conscious designs and historical components surrounding aesthetic, style, and the use of the things around us.

The first two weeks of class already have me thinking even harder about the things we design, make, buy, use, sell, throw away, repurpose. It was truly serendipitous that after a few other galleries, I wandered over to the Shaping Traditions: Folk Art in a Changing South gallery while deciding where next to spend my time. I had been planning to review a different exhibit, for a different class than Material Culture, but here it was in front of me, and there on the introductory panel was John Burrison, a professor at my school and friend of many of my professors, in a photograph with some of the pieces in the collection. I had a memory flashback and realized that I remembered learning that most of this collection--thousands of items--was his--he had been collecting southern folk art since the 1970s, and turned his collection and his lifetime of knowledge on folklife into an exhibit--a stunning and approachable work in itself.

From this leftover bit of mussel shell, you can see how they made buttons out of them. Incredible!

There on the same panel was a name that suddenly meant a lot to me: Henry Glassie. I had only just finished reading one of his books for my class, his 1968 classic within the folklife field, Pattern in the Material Folk Culture of the Eastern United States. I got really excited, and from there, it was several hours later before I noticed how much time I had been spending at each panel, examining each piece of folk craft, studying the selection of photos that accompanied throughout.

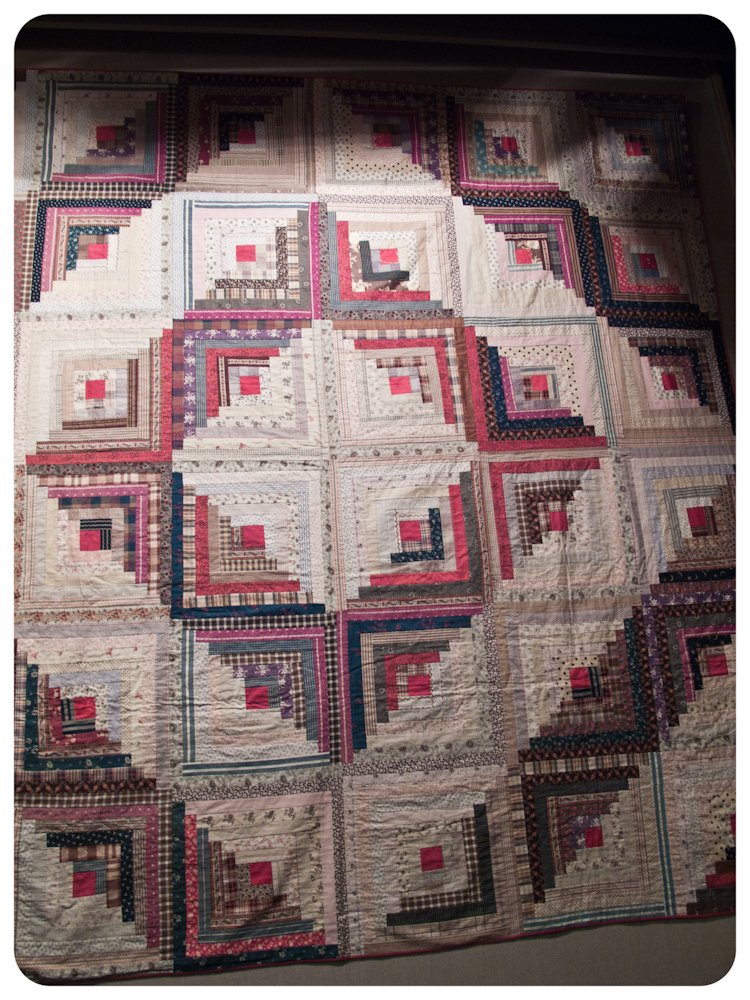

My favorite part, obviously really, was the section devoted entirely to southern textiles, quilts, motifs, and influential styles. The designers came up with a truly ingenious method to display and preserve the six quilts within the exhibit: each one rolled out on its own giant display board, once prompted by a visitor who pushes a button--which sits below a description of the type, material, quilter, and estimated year of creation. I must have pushed those buttons more than a dozen times, engrossed in their pattern and fabric choices, old as they were. Each was so beautiful, and they combined to tell a distinctly diverse story of the variety of quilting styles and influences that play into southern quilting.

The clever system within the exhibit that only exposes the quilts to light when visitors choose to roll them out--it's also fun to use!

The textile section had an essential "touch me" section, for those of us who were dying to feel the quilts and had to contain ourselves.

"Barn Rising" variation of a Log Cabin quilt, early 1900s

"Eight Point Star" variation with strips, by Estella Daniel, Emerson County, Georgia, 1930s

"Whig's Defeat," by Susan Loyd, Rome, Georgia, 1856

"Brick Work" and strip pattern, Annie Howard, Madison, Georgia, 1957

(Read on for a bit more about the themes of the exhibit; it's worth a few minutes!)

The exhibit was consciously created to revolve around its stunning artifacts, to tell the larger story of the relationship between folk craft and folk art in past and present southern life. The overarching thesis the exhibit aims to impress upon visitors is that there has been both continuity and change in southern folk art, and that the relationship within it—southerners and their handmade products—is an important component in the history of the South.

Craftsmen-made ladderback chairs

Subthemes arise when we look more closely at the organization of the exhibit, where the story begins to unfold. The exhibit is organized by subtheme, taking us through the various conversations, one stacked on another, that the curator wishes to share with us. The first message the curator needs to convey is a working definition of what “folk arts” are, which is explained in a number of display cases, via brief panel text, but more through the artifacts that have been selected to prove each specific piece of the definition. Folk Arts, we learn, are many things: they are learned traditionally; they are important community resources; they bring the past into the present; they are adaptable and flexible in shifts of human need; they can be both useful and beautiful; they are handmade in an inherited tradition passed down through generations. These axioms are expressed through a number of specific artifacts: homemade violins using both wood and metal pieces, or woven baskets that have more recently been woven with plastic pieces, or pieces that illustrate handmade characteristics against those of uniform, factory-made pieces.

The exhibit has an incredible collection of folk furniture, with all the requisite textiles, potter-made earthenware, and other pieces that defined home life in preindustrial Georgia.

The second subtheme moves us into the active use of folk arts in everyday life, reminding us that traditional, preindustrial southern culture did not draw a clear line between art and work—but that both were intertwined in each activity—sewing, farming, and cooking included. The exhibit addresses what makes southern folk art “southern” by discussing the interaction of European, Native American, and African cultural groups, and by telling the story of southerner’s lives: living off the land, and using hand-crafted tools to aid them. The third subtheme brings folk art home, in southern living spaces and decorative aesthetics; this includes an enormous section displaying domestic arts past and present, including some present-day artists—pottery, baskets, chairs, furniture, and textiles. The last subthemes take southern life “beyond subsistence”—into leisure activities, and finally, to the revitalization and change that has taken place since industrialization revolutionized the South.

Modern-day artists and immigrant groups who have added their cultural traditions to the South in the last half century are featured near the end of the exhibit space, proving that folk art in the region, while no longer necessary for our work or daily life essentials, is still an important part of our cultural lives; we are surrounded by the artistry and traditional techniques of those who continue to practice and pass on our folk arts. Shaping Traditions tells this story through the objects that define the subject.

Go see it.

Ben stopped by to say hi to my camera

Ben's note in the guest book. Haha. True statement.

This is what pure giddiness looks like.

Also: Nose-picking in the Metropolitan Frontiers exhibit