A movie about culture, to influence our culture today

How appropriate.

The 1982 film Diner was groundbreaking in that its characters spent a lot of time talking in a diner, and talking about popular culture. And it turns out that until the 1980s, filmmakers were generally wary of including popular culture references in their films. Immediately what comes to mind is Quentin Tarantino, and the films he has propelled with chatter, conversation around a table, or equally as often in his films, a dead body.

How appropriate.

The 1982 film Diner was groundbreaking in that its characters spent a lot of time talking in a diner, and talking about popular culture. And it turns out that until the 1980s, filmmakers were generally wary of including popular culture references in their films. Immediately what comes to mind is Quentin Tarantino, and the films he has propelled with chatter, conversation around a table, or equally as often in his films, a dead body.

An excellent article in this month's Vanity Fair explains all the hiccups, details, casting triumphs, and other lore behind the now-classic film (which I've never seen, actually, I shall have to fix that). Author S.L. Price credits Diner with having been the forerunner to the entire Bromance category of films, and Judd Apatow's entire career. (The film is also,incidentally, Apatow's favorite of all time.) Seinfeld, The Office, and Tarantino's dialogue sequences are all based on the same mundane nothings that occur in life--the stuff in between the big moments, dramatic episodes in life and in fiction on the big and little screen.

Author Nick Hornby was interviewed for the story, discussing the influence of films over time, including Diner, and he brought up something interesting, indeed, about what we consider to be on the list of "best films of all time":

'Influence' can be a tricky word. 'When people talk about influential movies, what did they influence?' Nick Hornby asks. 'It's a very good question. Come on, what did Raging Bull influence? What did Blue Velvet influence? Can you see it anywhere else? It seems to me those movies were sui generis--you can't see their influence anymore. People just mean that they were really good movies. Whereas Diner did start a way of thinking about writing about popular culture. It did create a mindset where people like me and Jerry Seinfeld and all sorts of others thought, Oh, I can see how to do this stuff now.'

Another wonderful bit came from Stephen Merchant, who with Rickey Gervais, created the BBC series The Office.

'Ricky and I often talked about how, in The Office, we featured life's boring bits--the bits other shows would cut out,' Merchant says. 'That's something Diner taught me: that there is charm and interest and value in capturing the way real people behave. You don't have to have 90 minutes of shouting or fist-fights or blue aliens. Eavesdropping on the people who drink next to you in your local bar can be just as interesting.

Merchant is speaking my language. I have long thought that walking into any institution of dining or entertainment or place of work, there are so many stories and lives that I do not know, and how interesting some of these lives must be. I love eavesdropping and hearing tidbits of lives I won't be a part of. It's all very intriguing.

And it is probably one of the reasons that I was initially mesmerized by John Travolta and Uma Thurman sitting in a diner talking about a $5 milkshake, when I came across the scene on a random cable channel sometime around age 16. No one ever told me, hey, you should watch this movie about drug addicts, thugs, double-crossers, hit men, and their wives. I was vaguely aware of Pulp Fiction having been considered a good movie. But I basically discovered it, and eventually sought it out, on my own. (And later on became, arguably, a Quentin fangirl.) It is one of the most amazing, well-made, truly great and groundbreaking films I have ever, ever seen. I eventually bought it on DVD after never successfully catching the whole thing on TV. And let's be honest, how do you even properly experience Pulp Fiction on cable television? The L.A. underbelly sans cursing, drug overdoses, and rape? Why even bother to air it?

But while Seinfeld mass-marketed Levinson's [the creator of Diner] focus on minutiae, the ultimate film geek made it cool. In 1994, Quentin Tarantino's Pulp Fiction won praise for its ultra-stylized, ultra-violent take on the L.A. underworld. But what made the movie click were the jazzy back-and-forths between hit men John Travolta and Samuel L. Jackson about Big Macs, foot massages, and the virtues of eating pork like 'that Arnold on Green Acres.' Tarantino's genius, first demonstrated in 1990's Reservoir Dogs, sprang from the decision to make his reprehensible characters sympathetic--to make the audience laugh in recognition while wincing at the blood--through dialogue that any truck-driver would recognize. Guy talk. Diner talk.

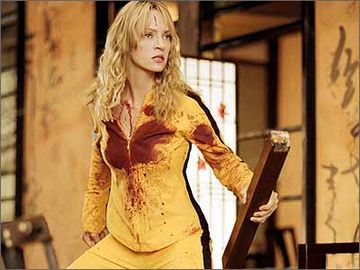

Next to this paragraph in my copy of the magazine, I wrote, "Yes. Yes!" I wrote it twice, because of how strongly I agree with this statement. He is not the first to make this case. But that is exactly what Tarantino does--he invites you into the lives of unsavory people and shows you all the ways they are human, too. The Bride aka Black Mamba aka Beatrix Kiddo, the protagonist in the two-part Kill Bill movie is an ex-assassin who kills about a hundred people in an act of vengeance, after her daughter and husband-to-be are murdered by her former assassin coworkers. Ridiculous premise, perhaps, but a human motive and a lot of human action takes place among the samurai sword fights and people-hunts.

Next to this paragraph in my copy of the magazine, I wrote, "Yes. Yes!" I wrote it twice, because of how strongly I agree with this statement. He is not the first to make this case. But that is exactly what Tarantino does--he invites you into the lives of unsavory people and shows you all the ways they are human, too. The Bride aka Black Mamba aka Beatrix Kiddo, the protagonist in the two-part Kill Bill movie is an ex-assassin who kills about a hundred people in an act of vengeance, after her daughter and husband-to-be are murdered by her former assassin coworkers. Ridiculous premise, perhaps, but a human motive and a lot of human action takes place among the samurai sword fights and people-hunts.

One of my favorite characters in the film(s), Bud, Bill's brother, is basically scum of the earth. But there's a scene where we see the inner workings of his job--as a "bouncer in a titty bar"--and we feel genuine sadness and pity for the life he lives, and almost entirely in solitude, save for his nasty boss and the chicks in the bar (the ones with the important tits). Some of the best bits in any of Quentin Tarantino's films are the ones with the minor characters. Son Number One and the Sheriff appeared in the El Paso wedding chapel in Kill Bill and then again investigating the zombie attacks in Planet Terror--the first of the two films that make up the 2007 Rodriguez/Tarantino project Grindhouse. They are great characters.

One of my favorite characters in the film(s), Bud, Bill's brother, is basically scum of the earth. But there's a scene where we see the inner workings of his job--as a "bouncer in a titty bar"--and we feel genuine sadness and pity for the life he lives, and almost entirely in solitude, save for his nasty boss and the chicks in the bar (the ones with the important tits). Some of the best bits in any of Quentin Tarantino's films are the ones with the minor characters. Son Number One and the Sheriff appeared in the El Paso wedding chapel in Kill Bill and then again investigating the zombie attacks in Planet Terror--the first of the two films that make up the 2007 Rodriguez/Tarantino project Grindhouse. They are great characters.

Learning about Diner was important to me, as I did not undersand as I do now how significant a shift there has been in what chatter takes place on television and in the movies. The irreverence of many of my favorite shows and movies would not be there at all without the changes in attitude and approaches to dialogue that occurred thereafter. Do you think Sofia Coppola could have gotten away with Bill Murray and Scarlett Johansson spending an entire film in quiet spurts of dialogue followed by longer spurts of silence and bonding--and a great soundtrack--without these shifts? Lost in Translation would not have been green-lighted.

Now, which of these should I go watch right now?