"This is part of our family history" - meaning in the AIDS Memorial Quilt

I want to share with you the meaning behind Parnell Peterson's quilt panel, which is in Block 2744 of the AIDS Memorial Quilt. I have learned so much about Par through his sisters and my mom since I first visited his panel in January, and much of it shall remain in my unpublished writing and memories. However, I think his quilt panel is an extraordinary example of something that occurs on a larger scale within the enormous memorial--the largest piece of folklore in the world--and that is still expanding with new panels submitted every year. (It currently contains over 48,000 panels.) You can look at a hundred quilt panels and see things that look similar to Par's, which is pictured here.

Now I want you to read his sister Margi's description of their process, each piece, and the meaning of it all:

Making Par’s Quilt panel was a wonderful and healing endeavor for all of us – indeed, many of us. We had sent out a letter, inviting friends and family to make a small square that we could then incorporate into the larger panel. We got so many, with so many wonderful stories attached that we soon realized that we would have to make a double panel. The top of the panel symbolizes the Northern Lights, which became our symbol for Parnell, after an amazing and miraculous experience we had with them, the night Par died. (That is a story in itself, which I will share at another point.) We had decided to use a tree as a symbol of life continuing, nature, the land that Par loved in his professional life, as well as personally, having grown up in the UP! The photo we placed in the middle of the upper panel was the inspiration for the whole thing – and then at the last minute, we decided to attach it because it is so beautiful and fit so well. The inscription, “Your Light Shines On” refers again to the Northern Lights and our belief in his continued presence which lights each of our lives and always will. We then decided to put all the small squares on the lower panel and to run the roots of the tree down through and amongst them….symbolizing that this is the ground and foundation from which Parnell came, grew, was nurtured, and lived – all these people who were somehow a part of him. The hands at the bottom of the tree are those of immediate family members, including niece and nephew, protecting the memory and holding it close. We loved how it turned out! We each actually have a small photo album of each square and the story that came with it…such love and grace in each one!

There is a stunning amount of meaning put into every, single, thing in this panel. Knowing how much thought went into his, I imagine similar kinds of deep meaning in each quilt panel. It makes me stop, linger, ponder and examine each square that I do see even more closely. What was compelling and inspiring these people, or this person, who loved this other person, who we are now remembering? If even the dyeing of the denim fabric behind Parnell's panel had boundless personal meaning for his family, imagine this same thought multiplied by the number of people memorialized on this Quilt.

The past two Mondays, I have confirmed a few more of these meanings, backstories, which remain so mysterious and anonymous to most people who visit the Quilt on display, or view its panels online. I have been volunteering to offer my small amount of help to the larger effort of bringing the Quilt back to Washington, D.C., where it will be for almost four weeks this summer. The first team departs this week to bring the acres and acres of fabric to the Mall, the Smithsonian, and various other locations in the capital.

My job has been quite extraordinary: check, assign a working panel number, and document each new square that has arrived this year, so that these unfinished panels may also make the journey to Washington and be sewn into the larger Quilt during the ceremonies and viewings. It will be a very active way of sharing the Quilt, having these newest panels sewn in as part of the displays themselves. So I also go through and record any additional things that arrive with the new panel, like a letter, photo, or other momento.

Last week I read a letter from a woman explaining that this panel was made in memory of her mother, who died in 1994 or so. But it was made not by her--it was a surprise from her fiance. It was he that was also going through the sadness; I don't even think he knew her.

Today I read a letter from a mother asking forgiveness for "mistakes" or "imperfections" in her panel, which she submitted in memorium of her son, Scott, who passed away in 1997. "I've never done anything like this," she wrote. It is so interesting to me to read people's unsure, honest thoughts when mailing in something so personal, so much a part of them. Margi, Parnell's sister, said actually handing over Par's quilt panel, after all that work, was much more difficult that she anticipated. Almost like giving up a piece of Par himself, some of that closeness and memory.

It makes me smile, as I cannot imagine anything that would be similar to submitting a panel to the AIDS Quilt; of course this is new territory. But she described the lovely details she incorporated into her son's panel: dark denim and light denim from the pants of his older and younger brother; velour from his niece's jacket, and a patterned piece of his maternal grandmother's blouse. Once I opened up the panel to see, I was struck by her use of the bits -- not as a random assortment, but as mountains in the landscape she created for him out of fabric--he was also a lover of nature. Again, I am struck by the meaning behind some simple stitched mountains.

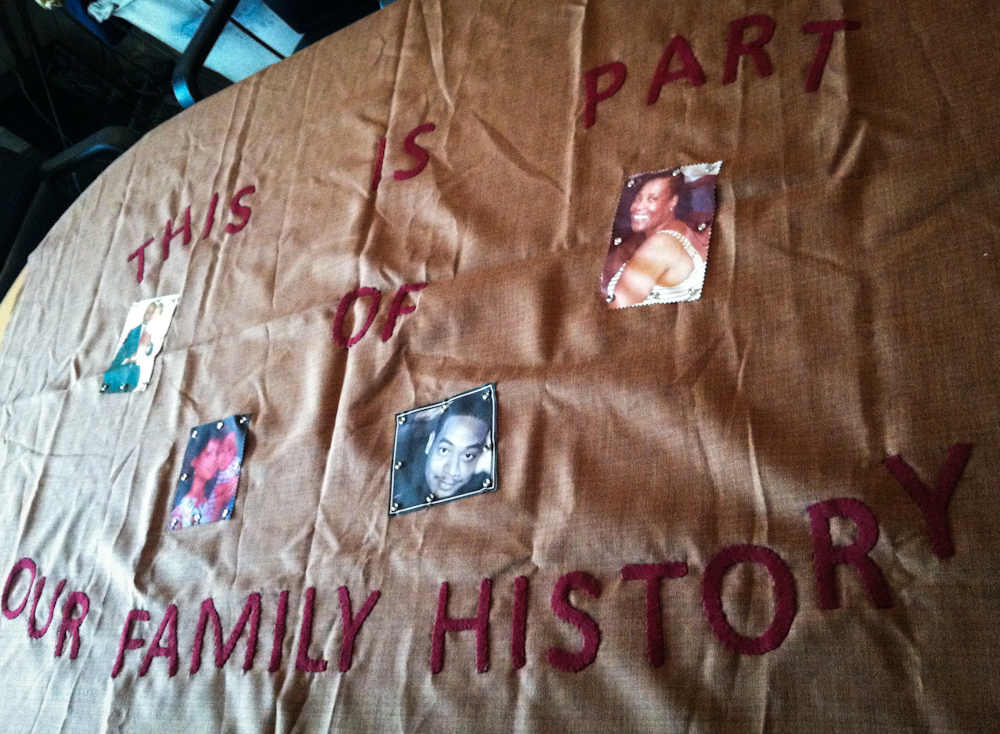

Another of my favorites, steeped in meaning and yet so simple, is the family who submitted several squares for individuals in their family who have been taken by HIV/AIDS, and this other panel to accompany them all in the Quilt. "This is part of our family history," it says simply.

This is absolutely so. I hear a lot of family histories in my work at the National Archives. Every other person has a family tree to rattle off to me, a Native American chief ancestor, and several on the Mayflower. HIV/AIDS is such a significant part of human history, and it is now part of the family histories of so many.

"Life in the Age of AIDS is the Story of Us All."

This is the adage that hangs printed in the front offices of the NAMES Project Foundation, the headquarters and keepers of the AIDS Quilt. This sentiment speaks so much truth, and relates exactly to that family's panel, an actualization of their grief, and their insistence on making sure this remains a part of their story. Because we all own it.

I cried only once during 5 hours of processing new panels. I opened one up, unfolded it gently on the table, and pictures of a young man stared back at me. I read his lifespan: January 5, 1987 to September 11, 2010. He is, he was, my age. He was lost to AIDS at the age of twenty-three. How does this still happen? I felt outrage, sadness, shock, anger, thinking we were at least more equipped to handle HIV in the 21st century. But Ricardo did not survive it. This is why the Quilt is still important; and it is not a problem existing only far away from us, in Africa or in the 1980s. We are not immune in the United States and it is crucial that young people have the information they need. Seeing Ricardo's square was a reminder, a wake-up call that this is not an abstract health crisis. He died, and he was my age.

What are the words to properly explain this, to come to terms with it, to understand? I can only keep offering my time, skills, and love to a cause.