Georgia: A State's History in Peril

The Archives of the State of Georgia is another casualty of the recession we have been in for the last five years. Nearly every state is hurting, in massive debt, and looking for ways to avoid default, cut their budgets, and reassess what matters. Obviously there are some highly important things the states provide, and must keep providing, including some of the things keeps respective citizens barely sustained above water in their own lives. And while it might not seem like an item of crucial signifigance, I assure you, the Archives of the state does matter. Fifty years from now, the history of Georgia will be in its own state of crisis.

The Archives of the State of Georgia is another casualty of the recession we have been in for the last five years. Nearly every state is hurting, in massive debt, and looking for ways to avoid default, cut their budgets, and reassess what matters. Obviously there are some highly important things the states provide, and must keep providing, including some of the things keeps respective citizens barely sustained above water in their own lives. And while it might not seem like an item of crucial signifigance, I assure you, the Archives of the state does matter. Fifty years from now, the history of Georgia will be in its own state of crisis.

Georgia is the first of all fifty states to close its archives to the public. It is due to necessary budget cuts that were required of each branch of the state government. The Archives is under the Secretary of State's office, and its budget, already emaciated from year after year of cuts, is finally getting the big slash. It made the New York Times earlier this month:

In November, a round of government budget cuts will reduce the staff to three, one of them the maintenance man. Thousands of documents that pour in every month are likely to languish because no one will be available to sort through them, archives officials said.

Archives are the physical, historical records of any entity, and in this case, we are talking about every significant document ever created by the state, from 1733 to the present. We are talking about milestones and historic markers in the stately lives we lead. If I learned one thing working at the National Archives--which, logically, holds the records created by federal agencies working in various states around the country, it is that people don't often come in contact with the federal government throughout their lives. People would come in every single day asking to see records of their families, and honestly, we didn't have much for them. We have the "big stuff," I liked to call it: the decennial censuses 1790 - 1940, immigration records 1906 - 1991, and military records for wars from Revolutionary to Vietnam. If you weren't a naturalized citizen or a veteran--or your family members weren't--then we really only had some census records for you to ponder.

Most people really wanted the state-level documentation of their ancestors' lives. That's the birth, marriage, and death records. That's the land grants, the tax records, the wills and deeds for sale. And down in Morrow, Georgia, the two facilities--federal and state--are right next to each other and share a parking lot, though they are technically not affiliated. But that did not stop people from bring furious with me when I told them the State Archives was only open Fridays and Saturdays, due to budget cuts. This was already the sad state of our Archives, open two days a week. Write your Congressman, we would tell them, when they were especially upset. Now, beginning November 1, it won't be open any days. It will be by appointment only.

When I first read this, I thought about it realistically: okay, well this is a recession and the state had to make some cuts and they have to come from somewhere, right? The genealogists will have to get over it. But then I read the New York Times article and it hit me like a lightning bolt, the crucial part of the archival process that I was forgetting: the records must be processed, the new records that come in every year. Without the staff to do this (it would be utterly impossible for even a large staff to handle it all, let alone two solitary archivists), the records arriving there now, this year and in the next however-many years, will simply not be addressed. They will be stored, yes, but without someone to go through and make sense of the collections, future researchers have absolutely no chance of doing this themselves to try to cull historical and important information about our state's dealings and doings in any realistic timeframe. It could take years to dig for the series of records one might be seeking. It means research of any real means will be impossible in this state. I mean the real, big historical research: documenting the state through time. But I also mean regular people's genealogical research, too.

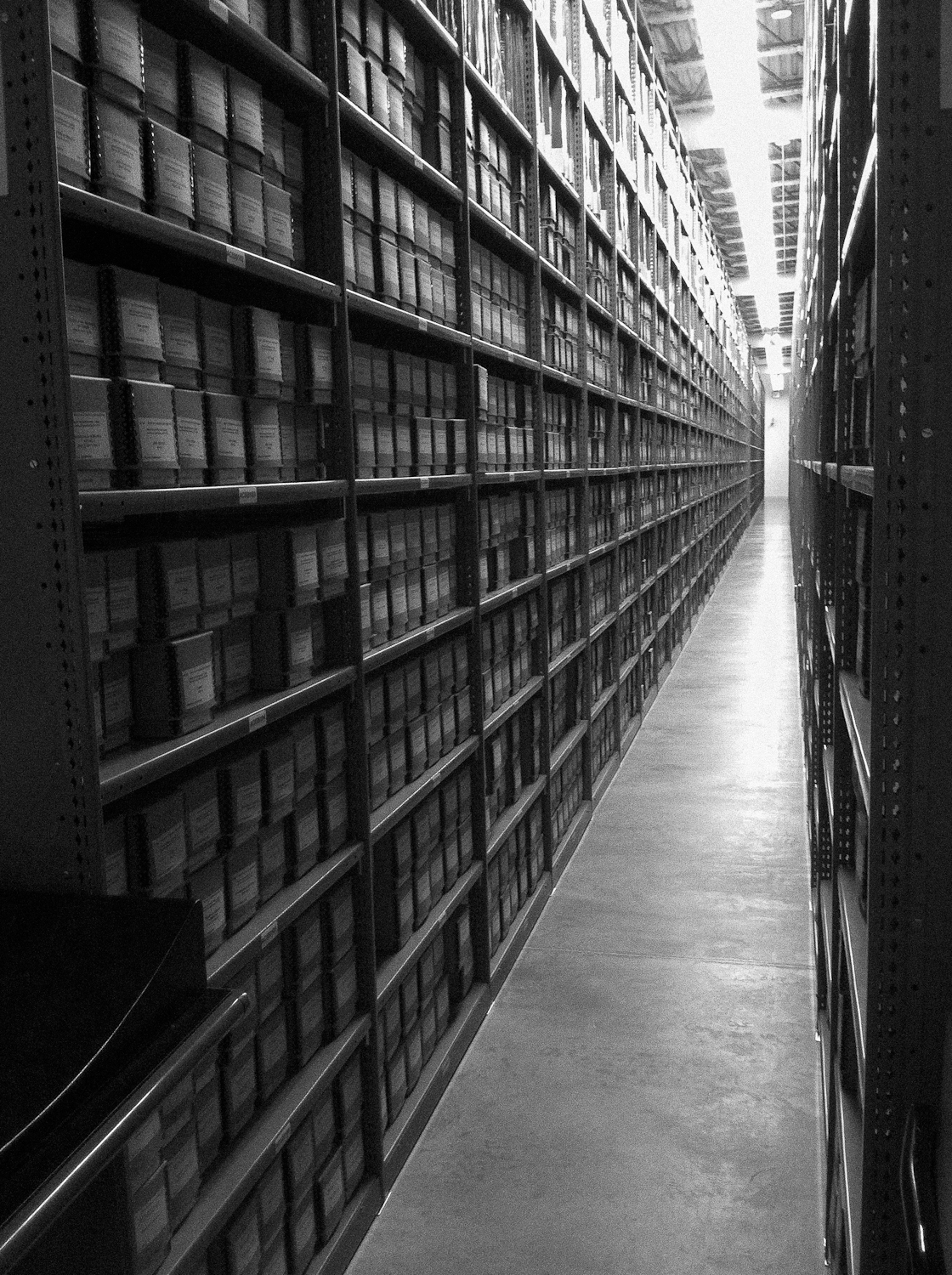

Just so we're clear about how much sheer square footage of boxes of records I'm taking about here:

The volume of paper records held by state archives jumped to more than 3.9 million linear feet in 2012 from about 2.5 million linear feet in 2006, according to a survey by the Council of State Archivists.

Add to this the amount of born-digital records state governments are creating today (coupled with changes in process and how to manage and store all that fast-changing technology), and you have a staggering amount of material to oversee. W. Eric Emerson, the director of archives and hsitory of South Carolina, was quoted in the Times article with the most succinct statements on the subject:

His fear, like that of other archivists, is that “20 or 30 years from now, this will be a period in which numerous government records were lost.”

It’s more than just adding server space and storing files shipped in from other agencies.

“That’s like taking 200,000 documents, throwing them in a Dumpster and telling a researcher: What you need is in there. Go get it,” he said.

I guess that's what I've been trying to explain. Throwing 200,000 documents in a dumpster in no apparent order and saying, sure, go for it. And good luck.

Our best hope is that in the years ahead, budgets will be balanced by economic improvements and smarter, more sustainable and frugal state fiscal plans. Hopefully this is sooner rather than later, so we can keep the history of the state from what stands now to be an estimated thirty-year "dark ages" period, void of historical context.

UPDATE 10/20/2012: This week, Governor Deal has made an agreement with the Secretary of State Brian Kemp to allot an extra portion of money that will keep the archives open six days per month through the rest of its fiscal year. See here.