Reading Robert Traver: a big murder in a small town

About a month ago my Dad and I sat down over a couple days, with the tape recorder, and he told me a few stories about his days as a detective in the Michigan State Police. We spent most of that time discussing one particular murder case, that he always thought would make a great book, but which he has decided he'll never get around to writing. He also decided that he trusts me with the story, and has handed off that book idea to his daughter. I will attest that it's a great story, rife with great characters that I can explore from many more angles as I turn this tale into fiction. Names will be changed; the region, however, where this 1988-89 investigation took place is far too curious, beautiful, and distinct to change for the purposes of fictional blurring.

The Upper Peninsula of Michigan (the U.P.) is the place I was raised, for the first ten years or so of my life, at least. It is the place where my family lives, and it is a strangely remote place to return to, and unique in both its grand beauty and also in the deep-seated love its citizens have for it. There is a culture too, that must be maintained: of iron ore and unmistakable accents -- "oh yah, ya say?" -- of pasties and Nordic lineage and a specific kind of adoration for the seclusion that corner of the U.S. maintains. It is only quite recently that my phone hasn't switched over to analog mode by the time I drive that far into the wilderness.

So I'm writing a fictitious story inspired by a real murder and subsequent investigation, and to be honest I would be flying entirely blind were it not for the impressive amount of real events that I have already sitting in my notes, to write about. There is a real story here compelling me to put words on the page, and it is comforting to know that I kind of already know the larger arc of the story, even if I haven't met all the characters yet, or developed their personalities beyond my perceptions of them has I listened to the events unfold. I don't often read crime novels; in fact, I rarely read fiction. These facts also contribute to the feeling of floundering, staring at the page wondering how to write actual dialogue, that beast which drives the story, which introduces the characters and what they think, do, and mean. Naturally, I asked my Dad for any advice or examples he could provide to light the way for me. He had two.

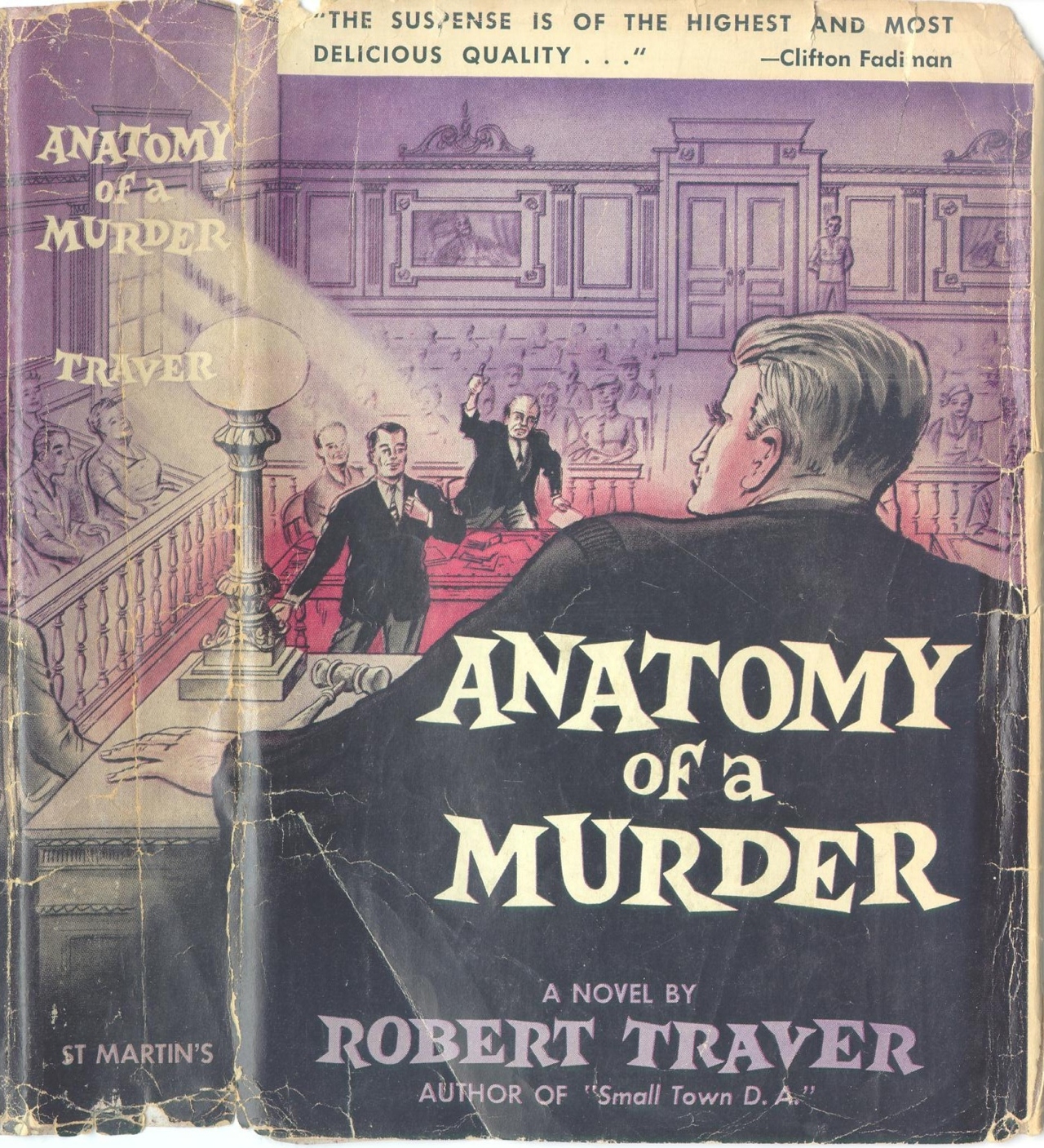

One of them is Robert Traver's Anatomy of a Murder.

The book was published in 1958, based on a real murder trial that took place in 1952, in Marquette, Michigan, and was made almost immediately into the more-well-known 1959 Jimmy Stewart film of the same name. I am anxious to watch the movie (I will in the next few days) because my Dad said most of it was filmed in the U.P. and many spots, like the jail and the courtroom, are still in existence. In the case of the courtroom, it's still in use today, and is in fact the same one that heard the trial of the man and woman in the murder case I'm writing about now. It was and still is one of the biggest things to happen in the U.P. in terms of outside attention. It was a big deal. (Parenthetically, my Dad once recovered the very murder weapon, years later, when it turned up along with some other stolen items he recovered in his work with the State Police.)

Robert Traver was the penname of the Michigan judge John Voelker, who was a Michigan State Supreme Court justice and a Hall of Fame fly fisherman. He had a little fishing shack he maintained for years as he got older, keeping it a secret to most people, but my Dad was one of the people who had a key and would check in on it for him. (He died in 1991; both Voelker and I were living in Marquette County at this time, though I was oblivious to the fact back then.)

I finished reading the book today, and I couldn't help but feel a bit of a kindred spirit to Voelker, not in the sense that we share the same profession (him, law, me, history) or interests (Voelker, fly fishing, Edens, quilting), but in the sense that he found himself in a career shift, a season of a spare bit of downtime, writing a story based on actual events--a murder case that took place in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan.

Days after the murder of a bartender at a small hotel in the county, the locked up murderer gets in touch with the ex-D.A. for Marquette County, John Voelker, who is himself unsure what his next professional step should be. He takes on the case, defending the army lieutenant who shot the bartender, and successfully acquits him; a jury finds him not guilty by reason of temporary insanity. It was one of the first cases to successfully use this reasoning, and it goes without saying it was a big deal -- a big media topic for the late '50s press of a small region filled with tiny townships. It's a highly-followed trial, and the trial is what Traver/Voelker focuses on most, along with his preparations and legal research. It is a fascinating glimpse into the mind of a trial lawyer preparing a risky defense, with colorful characters all around him, and more intrigue than one might think possible as the story unfolds, especially considering the simplicity of the circumstances when we first learn of the situation. Husband shoots the guy who allegedly just raped and beat his wife. We already know who did it, there's no shock there, yet we stay with Paul Beigler, the protagonist defense lawyer of this story, waiting with baited breathe to hear the final verdict, after hours and hours of grueling testimony, smart and snide courtroom arguments among prosecutor and defense lawyer, and the very questionable parties involved on either side of the thing. It gives the story even more gravity to know it was all based on real stuff, that Traver/Voelker himself lived through.

I was quite surprised how much I enjoyed this trial drama of a book. It has, after all, been a long time since 1958, and it would not take a stretch of the imagination to see a story about rape, lawyers, and barroom fights of the 1950s to seem quite dated compared to those same things in 2012. But very little of it felt old, outdated. And it was a great reminder to populate my own story with charming, intriguing, and complex primary and secondary characters. One of the most interesting things so far in the process has been watching which characters in this story I am telling are coming to the forefront, and what they are like, what makes them tick. Time will tell whether I can do them justice on the page. In the meantime, it makes me smile to imagine the Mister Robert Traver sitting at his own desk in Ishpeming where he lived, typing out page after page of his fictitious, based-on-real-events courtroom drama, wondering too if anyone else might want to read it.

As a side note, I read the whole thing on a Kindle, very non-1958. It was an experimental experience, to see if I would like the experience of an e-reader. I loved it.