The Way You Learn It

I’ve been learning about the Manding people of West Africa, and about the esteem to which ancestry is held in their culture. Not only does their jamu (specific lineage) determine their relative position to other people in the community, but that very same lineage connects them to the heavens and God. The way my teacher, a Liberian man, described it, in many West African cultures the ancestors are who listen to prayers, and send them upward to God. “Kind of like the Jesus Christ of Christianity,” he said.

In my History of Science class, we’ve been contemplating the world from an Aristotelian perspective. Remember, Aristotle thought the earthly world was composed of four elements: earth, water, air, and fire—and that a thing’s essence, rather than gravity, was what pulled it to its proper place within nature. The cosmos, on the other hand, was observed to be perfect, and was therefore composed of the fifth essence, or the “quintessence.”

In viewing things through Aristotle’s theories, the world was just as complicated as it is today, even though they had yet to develop the concepts of gravity, or chemistry, or the laws of inertia. So the ways of explaining things that puzzled humankind seem silly by comparison to the things we hold true today.

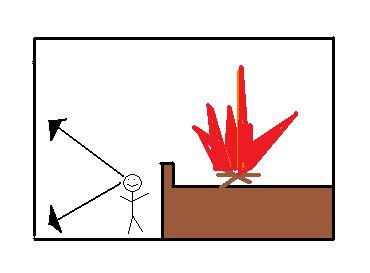

And the final thought that brought me to a point I will soon make came from Plato’s allegory of the Cave, which cropped up in class and conversation twice in the same day. To best understand Plato’s idea, see my rough drawing below:

The fire is blazing in the back of the Cave. There is a small precipice, and on the other side stands a man; this little man represents Mankind. He only looks—can only look—at the wall in front of him. What he sees in the world, in his little end of the cave in other words, is the reflection of the fire. What Plato means by this is that everything we see here is the shadow, the earthly representation of things which exist in a perfect form elsewhere. (The true form, the essence, can be seen by men who strive to find it through logic and reason, he proposed.)

When Plato’s cave was brought up for the second time in my day, it was because we were discussing how Man, inside his cave, might never want to turn around and see the “true” form of the world he thinks he knows. Just as most people shy away from great change, from stirring up their beliefs and lifestyles, little Man is very content to stare at his Wall, keep his perception of things just as it is.

And so, my point: in looking at the Manding people’s prayers to their ancestors, someone who knew and lived by western customs might learn about, think it’s interesting and different, but also think it to be silly and incorrect. But the thing is, someone in Mali might think the exact same thing about western traditions.

My Liberian professor told us about one of his relatives who died in the U.S. over the summer, and how the family members that are also living here buried him the American way, with a funeral home wake and standard gravestone. The relatives in Liberia were upset; was there going to be a feast, with a plate of food given to the gravesite as an offering to the ancestors? Well, no, that’s not how they do it here. Was the body going to be displayed in the home? No, that’s not allowed here. Then how could they be sure the body would be passed into the ancestral realm correctly? Bring the body back to Liberia, they demanded. No, that is way too expensive, we cannot do that. A clash of cultures, indeed. Whose method of burial is right? Is one or the other silly, or moreover, is one wrong?

Thinking like an Aristotelian, I see the world in a complex way, but definitely not complex compared to the way we explain things today. My professor said that when his children were young, it was much easier to explain to them that the ball falls to the ground because it is simply “earthy.” It belongs in its natural place, below water, air, and fire. How would you explain gravity to a child? It is much more complicated. But, gravity is also the theory we go by today. So, Aristotle was wrong. But his way of thinking made sense to a lot of people for a long time, nearly a thousand years. And though it seems silly to us now, during that time his theories explained many things that were confusing then. *

And the final thread, the shadows of Plato’s Cave, represents the way we see things, all of us, on earth. We see reflections, yet we see them as the absolute truth. The way each of us lives is comfortable to us; we are resistant to changing our location, or our job, or a friendship or relationship, or a house, or the foods we eat, or our religion, or our idea of truth.

But if you are right, then is everyone else wrong? If you stayed in the Cave, always looking at things as you’ve known them, when or if you ever turned around and saw the “true form” of the fire, might you say that it was silly? I’ve been looking at fire all my life; of course I know that this new form is just some obscure vision of fire. So, by this reckoning, even if someone were faced with the “True” version of fire, he would dismiss it because it was not like the version he knows.

From all of this, I glean that what is “right” to someone is usually strongly founded in what they have known for most of their life. Even if a man learns all the other burial customs in all the world, he would still somewhat adhere to his, think his own the most normal—or the least silly. But as Plato might muse, does that make it right? Is it the real Fire?

*Aristotle’s synthesis of the world has many more faucets than just the concept of the four elements—far more than I can give justice here, without getting off-topic. Please research his synthesis if you’re interested.