Modern-day "Peril"? Chinese language in American classrooms, and that long-standing friend-or-enemy dilemma

China has the second-largest economy in the world, a fact that looms ominously over the shoulder of El Numero Uno: the United States. And when you are as connected economically as China and the U.S., it behooves each side to attempt friendliness; it also means it would be nearly impossible for either side to start a conflict with the other, as the economies are so dependent on one another that any such move could bring collapse to both.

And perhaps the most important lesson for the United States to learn, the one it struggles with most, is coming to honest terms with the fact that China is not a democracy. It functions as a fast-paced consumer economy, and does allow more economic freedoms today (like job choice and sometimes location of residency, for example), without really having changed its governmental system at all; much has been written on this unique breed of national existence, this "socialism with Chinese characteristics," and so the basic system remains today--with obvious cracks and some severe humanitarian issues on its plate. America has trouble with this sometimes, this issue of engaging as an ally a country with fundamental differences from its own governmental policies.

Neither condoning nor condemning China's policies, though, it must at least be admitted that China cannot be ignored. Without condoning their humanitarian infractions, myself and many Americans have been able to learn about the Chinese people's language, culture, history, food, and customary idiosyncrasies; each American who speaks Mandarin Chinese is contributing positively to the larger relationship between these two economic powers, to the extent that it is hard for me to understand the neglect this language currently sees in U.S. schools. In urban areas, more is inherently available to students; but in smaller towns, like the one where I went to high school, French and Spanish are the only options, and only through the required level "two." (Let's not get into that larger discussion on our monolinguist nation.) Meanwhile there are 264 million children in China under the age of fourteen, going through school right now, and I'll give you one guess what language they're also learning. It just seems so very clear that we're putting our own children at a disadvantage for their lifetime and their job choices, if they are unable to compete with the bilingual Chinese children who can communicate in both directions in the business and politics of the twenty-first century.

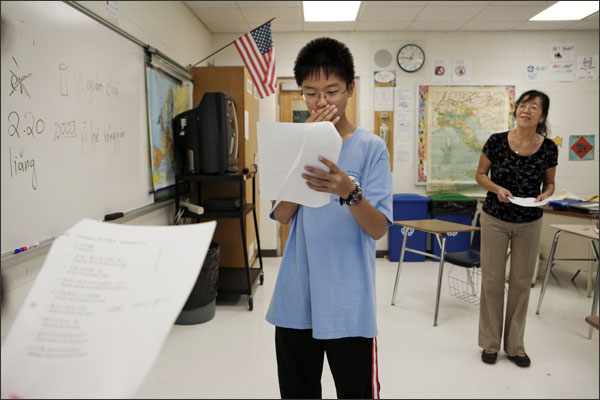

So the Chinese government has "stretched its linguistics muscles" this year by committing millions of dollars to U.S. schools to build Mandarin language programs in more K-12 schools. In a time of near economic crisis, and definite panic at least, in many schools across the country, this should be a welcome supply of funding, to get kids involved in their global world, and to infuse their studies with a new diversion--beyond their math, science, and social studies regulars. A connection with an Asian culture gives kids a much wider perspective on lifestyles around the world, connects them to a new level with Chinese-Americans in their communities, and, quite simply, gives them a "cool" language to study. Decoding Chinese characters is a thrilling revelation, for anyone who's studied the language.

So the Chinese government has "stretched its linguistics muscles" this year by committing millions of dollars to U.S. schools to build Mandarin language programs in more K-12 schools. In a time of near economic crisis, and definite panic at least, in many schools across the country, this should be a welcome supply of funding, to get kids involved in their global world, and to infuse their studies with a new diversion--beyond their math, science, and social studies regulars. A connection with an Asian culture gives kids a much wider perspective on lifestyles around the world, connects them to a new level with Chinese-Americans in their communities, and, quite simply, gives them a "cool" language to study. Decoding Chinese characters is a thrilling revelation, for anyone who's studied the language.

But naturally, given the menacing vision of China as an economic bully (granted, the fixed Chinese currency is a festering thorn in the side of economic negotiations and discussion), and given its less than stellar past of censorship, political freedom, and dissemination of information, there are bound to be cries of cultural infiltration: these Chinese will infect the minds of our kids! It's Yellow Peril for a new age.

In a recent article from Education Week, this issue was explored. Some see it as accepting resources from a country who will provide language, with a heavy dose of propaganda on the side.

That dust-up caught the notice of Chester E. Finn Jr., a former education official in the Reagan administration and the president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, a Washington think tank. He argues that public schools should not accept aid from the Chinese government.

“This is not an ally. This is the country on the planet from which the United States faces the largest and most worrisome long-term threats,” he said. “And for its government to be funding our schools to teach its language, I think, is an alarming and menacing development. And that our schools are welcoming this development strikes me as outrageous.”

Countering this, some educators see its value for the future or global relations, as well as for the schoolkids.

“It’s a great opportunity,” William C. Harrison, who chairs the North Carolina state board of education, said of his state’s program, to which China is expected to supply more than $5 million in direct aid and “in kind” services. “The best way to become globally competitive is to develop an understanding of those with whom you compete, being able to communicate with them, and being able to collaborate with them.”

He added: “We’re looking at the number-two economy in the world with prospects to be number one. ... I think it’s in our best interest to develop positive relationships.”

The key lies somewhere in the balance of being economic allies while respecting differences; we don't have the best reputation with that. Shortsightedness now will have a crippling effect on our country's standing in the future, and the people leading it then will be the ones in school now, learning minimal Spanish and French. Our world will look mighty different then; can we find those areas of change now, and adapt?

UPDATE 12/9/2010: Here is another article on America's trials and tribulations in building a Chinese language program in K-12 schools. From Newsweek: "America's Chinese Problem"