Ai Weiwei: A game of chess and China's elemental flaw

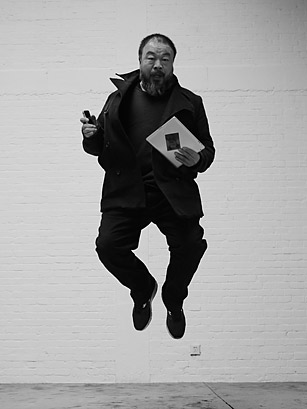

I have been fascinated by Ai Weiwei, the 54-year-old provocative artist and voice of dissidence in China, since May, when I heard an interview with his English translator on one of the my favorite podcasts. He was detained and questioned and kept by the government for 81 days this year, after his blog incited uproar from citizens who agreed and officials who saw him as a dangerous beacon. A tumultuous year has left him listed as one of Time magazine's People of the Year, as "The Dissident."

I find him interesting in his amorphous and fluid form and interpretation of art, connecting what we think of as "Art" with unconvention and with blogging and microblogging (i.e. Twitter and very brief forms of connecting online), combining his artistic impulses with his gift for words, writing pithy and prophetic bits. That's a kind of artistry I greatly admire, especially in the face of the Chinese State And All Its Men. There is quite a difference--and a kind of bold bravery I cannot imagine--between being an artist in a free and functioning democracy and being an outspoken artist in a state which does not value or embrace free speech, open access to information, or the fullest extent of self-expression--even if it means criticizing the men upstairs.

I have been fascinated by Ai Weiwei, the 54-year-old provocative artist and voice of dissidence in China, since May, when I heard an interview with his English translator on one of the my favorite podcasts. He was detained and questioned and kept by the government for 81 days this year, after his blog incited uproar from citizens who agreed and officials who saw him as a dangerous beacon. A tumultuous year has left him listed as one of Time magazine's People of the Year, as "The Dissident."

I find him interesting in his amorphous and fluid form and interpretation of art, connecting what we think of as "Art" with unconvention and with blogging and microblogging (i.e. Twitter and very brief forms of connecting online), combining his artistic impulses with his gift for words, writing pithy and prophetic bits. That's a kind of artistry I greatly admire, especially in the face of the Chinese State And All Its Men. There is quite a difference--and a kind of bold bravery I cannot imagine--between being an artist in a free and functioning democracy and being an outspoken artist in a state which does not value or embrace free speech, open access to information, or the fullest extent of self-expression--even if it means criticizing the men upstairs.

In his Time interview he was asked "What would you like to see in China?" This was part of his brilliantly explained answer:

We need clear rules to play the game. We need to have respect for the law. If you play a chess game but after two or three moves you change the rules, how can people play with you? Of course you will win, but after 60 years you will still be a bad chess player because you never meet anyone who can challenge you. What kind of game is that? Is it interesting? I'm sure the people who put me in jail, they're so tired. This game is not right, but who is going to say, 'Hey, let's play fairly'?

I've been studying China, Chinese politics, language, culture and history, for more than six years now, and my own thoughts on its political system have shifted at times between the two most polar ends of the argument: that either the "Capitalism with Chinese Characteristics" official plan has merit, is working, can improve and continue; or that China will inevitably give way democracy because it has already given much up to a free market economic system, and its people still hold memories of the extreme poverty and problems that stemmed from early plans in the early years after the Communist Revolution. People--around the world--have spent much time waxing on the future of China's political system. No one has explained its crucial fissure in its system so well as Ai Weiwei, himself a son of China, and the actual son of a revolutionary poet.