Genealogy and history: love & hate

My hate story

Recently I was talking about the main duties of the student archives technician at the National Archives, and it lead me into a tangent about perceptions of archives and the public’s idea that digitization is some panacea for records management, and an easy fix.

What I didn’t get to are my other duties at work. Besides holdings maintenance projects (the ones that started the tangent on the sheer number of materials we have), I also work in the public areas, assisting the public and researchers, and complete research requests for patrons who are off-site but need help. The first of these assignments takes up half of every workday, as it is the job of the students to assist the public so that the full-time archivists can get down to doing the projects and work they are here to do. Not that their duties don’t also revolve around aiding researchers and the public, but if someone has to sit in the textual research room while a researcher is here and she must not leave the room, well, that limits the amount of other activities that she can complete while essentially on lock-down. In this case, right now, I am in the text room supervising a researcher for the Corps of Engineers, and so I cannot leave the room; it allows for time to write journals reflecting on my duties here, for instance. Sometimes, if the timing is right, we can bring a project into the text room and work on it while we’re trapped in here.

The other room is the research room, and that’s the general public area, the one where you do not need a researcher card to enter, and pretty much anyone who can get past the security guards and metal detectors is allowed in there. It means we are safe from criminals, but we are not safe from idiots and crazy people, and we are especially not safe from… genealogists. I am not the first person to write (no, complain) about genealogists as the annoying part of the duties of a student employee here at the Archives.

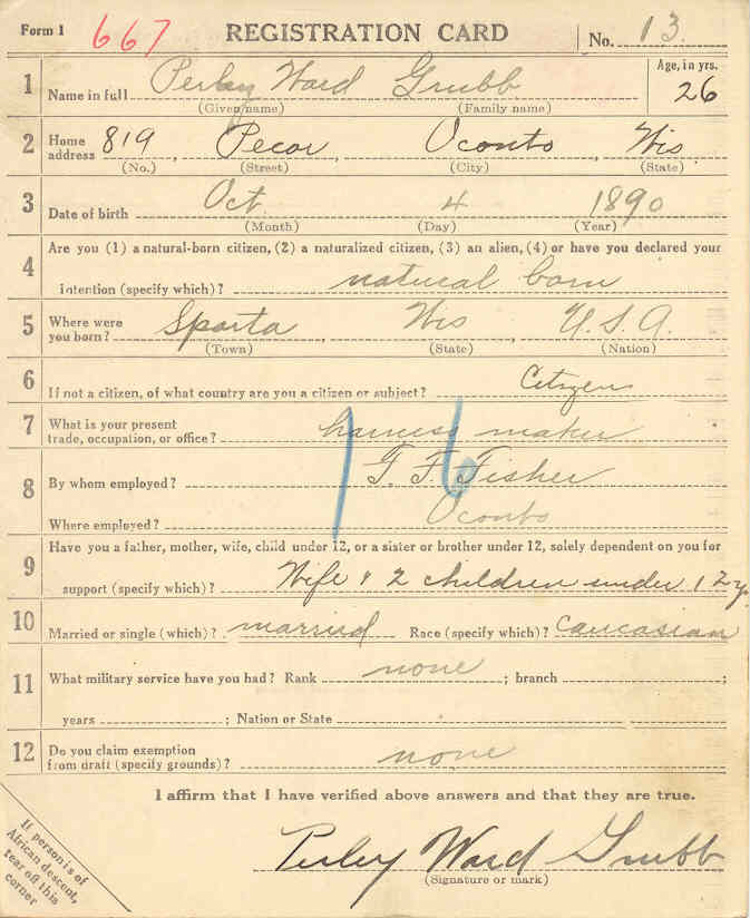

Not to sound snooty, but historians have a hierarchy, and genealogists are basically at the bottom, maybe even below the base marker. Family history is basically a nonstarter for most of us working here; it just doesn’t matter too much. We get a tiny thrill maybe the first time we see an ancestor’s draft card. That was the first thing I researched when I started working here, because they are commonly requested, and so I used it as a learning experience in pulling WWI draft cards. I found Perley W. Grubb, scanned his card, and refiled him with rest of the Wisconsin draftees. But where my family was positioned in history does not dictate either my feelings about history, nor the scope or basis of my research.

Not to sound snooty, but historians have a hierarchy, and genealogists are basically at the bottom, maybe even below the base marker. Family history is basically a nonstarter for most of us working here; it just doesn’t matter too much. We get a tiny thrill maybe the first time we see an ancestor’s draft card. That was the first thing I researched when I started working here, because they are commonly requested, and so I used it as a learning experience in pulling WWI draft cards. I found Perley W. Grubb, scanned his card, and refiled him with rest of the Wisconsin draftees. But where my family was positioned in history does not dictate either my feelings about history, nor the scope or basis of my research.

The problem is, most people’s families did really nothing much that would put them anywhere in the historical records. We have federal records here, and most people go their whole lives never really being really involved in federal functions. You fill out your census every ten years—that’s the main thing. Some people have military records—that’s another biggie. And if your ancestors immigrated or filed for a passport, they would also have filed federal records. But even then, in the case of immigration, they would have had to file their petition for naturalization in a federal court, and before 1907, it wasn’t required that they file them in federal court. So anyone who came to the United States in the nineteenth century could file in any level of court—county, state, federal, random Podunk local courthouse. And that’s if they naturalized at all; they might have remained nationals of their birth country.

We have research tools here for people to begin to find records their ancestors more commonly filed—vital records of birth, marriage, and death. Those are records filed with the state, and so are most often held by either the state’s historical archives or the vital records office—depending on how old they are and varying widely by state. People often get frustrated that before the twentieth century (and even in that one, in many cases) births were not recorded officially. If their great-grandfather’s birth was recorded on the inside of some Bible somewhere, I can’t help them.

It’s not to say that I wholly dismiss genealogy. I understand regular people’s need to see themselves in the past in order to make it meaningful for them. Genealogy is a significant historical experience for many people in today’s digitization-happy world. Part of public history is finding a way to make the past matter to an individual; this means including genealogy on the totem pole, for what value it does offer to a public craving connection. Historians whose focuses lie in larger themes, events, historical trends, and connections—oftentimes professional historians and scholars—don’t focus on minutiae of particular individuals unless they did do something significant or relevant to the subject of their study. Whereas genealogists go looking for a particular person to see if he might have done anything worth recording, historians find the things that were worth recording and then find out more about the people who did them. They start from different points, and work in opposite directions.

I understand though, that a large portion of the public we serve is here to do just that, to find their family. So I work in the research room, patiently helping octogenarians use the printers and computers, and try my best to let them do their own research even when it means teaching them how to move backward and forward on an internet page. (Yes, really.) We don’t do the research for them, we give them tools, indexes, direction on where to begin and what kinds of records will serve their needs best, and then we let them loose.

Once you’ve heard about Great Aunt Gertrude once, you’ve heard about her a hundred times. I cannot tell you how boring it is to hear someone rattle off names in a complicated web, as if I am going to remember or care how their whole family tree is organized. Funny anecdotes to them are a dime-a-dozen to me; but I try not to let my eyes glaze over, and always listen politely for as long as seems normal before bowing out and into my little glass room to hide (which doesn’t work so well in a glass room). Also fun: I can no longer count on two hands the number of people who’ve told me they are related to someone who came over on the Mayflower. This comment is my single biggest pet peeve of working in the research room, bar none. First of all, it’s probably not true; there are so many generations to prove unequivocally. (And there were not that many to survive, if you recall.) Secondly, it truly makes no difference to me whether your long-long-ago ancestors happened to live, even if it was in a colony that is super-famous and iconic in American history. You’d be more interesting to me if YOU have been on the Mayflower. Let’s talk about that!

Once you’ve heard about Great Aunt Gertrude once, you’ve heard about her a hundred times. I cannot tell you how boring it is to hear someone rattle off names in a complicated web, as if I am going to remember or care how their whole family tree is organized. Funny anecdotes to them are a dime-a-dozen to me; but I try not to let my eyes glaze over, and always listen politely for as long as seems normal before bowing out and into my little glass room to hide (which doesn’t work so well in a glass room). Also fun: I can no longer count on two hands the number of people who’ve told me they are related to someone who came over on the Mayflower. This comment is my single biggest pet peeve of working in the research room, bar none. First of all, it’s probably not true; there are so many generations to prove unequivocally. (And there were not that many to survive, if you recall.) Secondly, it truly makes no difference to me whether your long-long-ago ancestors happened to live, even if it was in a colony that is super-famous and iconic in American history. You’d be more interesting to me if YOU have been on the Mayflower. Let’s talk about that!

The most frustrating thing about working with genealogists is when they get angry, upset, or even cry over not being able to find much about those farther back in their family tree. I had one lady in tears at 4:45 one afternoon, because an ancestor she had been researching twenty-five years was still eluding her. He was drafted from Michigan into the Union army during the Civil War, and then she knew that the family received record that he died. She was distraught that there was no record of anything in between. Ma’am, I wanted to say, what the heck else would he have filed with anyone? He was at war. Unless he wrote some diary that somehow made it back into the arms of his family after the war, which is highly, crazily doubtful, there would be nothing else. He fought in a war and he died. That corner of the tree is complete. I am sorry if that is unsatisfying. In my experience, genealogy is highly unsatisfying, because it is so unlikely that your ancestors left much of a paper trail.

We make more of a paper trail these days, but it’s technically an electronic trail. Maybe in one hundred years, my Amazon Wishlist will provide a descendent of mine with endless insight into what I was like. They will also be able to read my Twitter feed, which I do think is very interesting to ponder. I so wish I could read the Twitter feed of Young John Allen, or those sent among the members of a nineteenth century quilting group. But until some of those things become “history,” for now we have the United States census, where you can see interesting things like whether or not your ancestors spoke English and were or were not the head of the household. (Am I coming across here as scathingly sarcastic? I do hope so.)