On Atlanta's traffic issues and the dismal hope of a better future: In which I present a scathing criticism of the state and the metro counties

I know the Atlanta/Metro Area Transportation Referendum is old news; the vote was July 31, 2012, and it went down in a blaze of glory. Citizens again voted against solutions to our clogged traffic and lack of alternative transportation options. The plan was not perfect, and in fact still included for many surrounding metro counties, plans for more roadways as part of the new options. (Sorry, say what? What??? There was really nothing better you guys could dream up? It's 2012.) But it still makes me really sad for this city, and mad as a citizen who loves it, that we have doomed ourselves to upwards of fifty more years in the traffic quagmire, while our population is expected to increase by about 3 million more people by 2040. Sounds awesome, guys. Can't wait for the daily connector traffic with those extra people beside me, too! But I did feel some hope when I read my August 2012 issue of Atlanta Magazine, which was their inaugural "Big Ideas" issue, including what the editors dubbed their "Groundbreakers," the big things Atlantans and local planners and companies are doing to make this city amazing. I think this is a great city; it has imaginative people, a colorful and quite distinct history, a pretty awesome climate (all things considered), and it's arguably the hub of business and culture in the southeastern United States. That's a big deal; this is where companies set up shop if they want to have access to the burgeoning southern region, which has finally risen--for the most part--out of its difficult historical economic and social stagnation, which plagued the South from the inception of the United States until roughly the end of the Jim Crow era.

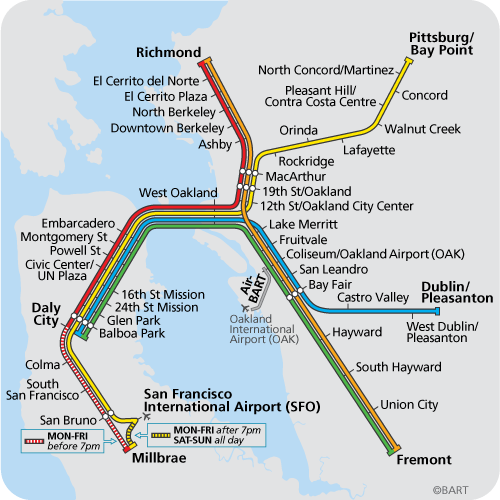

And yet we still had to screw up further potential by a fissure that has long cursed Georgia: the legislative relationship between the state (and often, the rural communities throughout the state) and the city of Atlanta. Harkening back to the days of the County Unit System (a topic for many blogs and many books, indeed), those outside the city--and the lawmakers who represent them--are often hesitant to spend time and money doing much that could improve its largest economic asset. That is exactly what has happened historically with the budding and dying and budding and dying of transportation options and alternatives in Atlanta since the 1960s, when cities like Washington, D.C. and San Francisco were also planning their subways and rapid transit systems. So, we all know where DC and SF stand today, right? And Atlanta, too.

Learning this particular comparison was a revelation, that all three of these transit systems were conceived and planned in the same era; I've used D.C.'s subways and they're wonderful. I can't vouch for San Francisco. But I certainly have an opinion about Atlanta's. And it turns out, the anemic rail lines we have today are a direct result of politics, and people disagreeing, and counties (counties who are part of the metro area, and have a responsibility to the city they depend on and the people who live in the counties) bailing on what once would have been a cohesive plan for a second viable commute option.

I'm looking at you, Cobb County. As my home for five years, I resent the choices your representatives and citizens made long ago, in a little mess that culminated in the Transit Compromise of 1971. It diminishes our entire reputation as a city; I want to believe this city can be even greater, but this is a bit of an important black mark on our future. I might sound a little bitter, but it's nothing compared to the scathing little article assessing the situation in Atlanta Magazine:

Like ghosts rising out of a Confederate cemetery, Atlanta's past lapses in judgement haunt the region today, leaving a smoky trail of suburban decay, declining home values, clogged highways, and a vastly diminished reputation.

At the heart of the rot eating at metro Atlanta is the Mother of All Mistakes: the failure to extend MARTA into the suburbs. It wasn't just a one-time blunder--it was the single worst mistake in a whole cluster bomb of missteps, errors, power plays, and just plain meanness that created the region's transportation infrastructure.

As we look at the future of Atlanta, there's no question that battling our notorious traffic and sprawl [!!!!!!!] is key to the metro area's potential vitality. What if there were a Back to the Future-type option, where we could take a mystical DeLorean (heck, we'd settle for a Buick), ride back in time, and fix something? What event would benefit most from the use of a hypothetical "undo" key?

The transit compromise of 1971.

I read this whole article and scribbled all over in the margins my own notes (as I do in practically every piece of literature I read, of any kind). Next to this whole intro, I wrote simply, "Ouch!" And then I felt excited. Yes, Atlanta Magazine, please harshly rip this apart. Represent those of us most disgruntled and angry and seeking options that do not exist because of the decisions made by voters and politicians decades ago, representing a far different Atlanta than exists today. Thank you, most seriously, for publishing this article.

The original plan for public transit, MARTA, was to include five metropolitan counties: Clayton, Cobb, DeKalb, Fulton, and Gwinnett. After several failing votes, the final plan would be for only two of these counties, Fulton and DeKalb--the two the constitute the city of Atlanta. Already, really it was set up for anemic failure. The article explains the issues:

Before we get into the story of what happened in 1971, we need to back up a few years. In 1965 the Georgia General Assembly voted to create MARTA, the mass transit system for the City of Atlanta and the five core metro counties: Clayton, Cobb, DeKalb, Fulton, and Gwinnett. Cobb voters rejected MARTA, while it got approval from the city and the four other counties. Although, as it turned out, the state never contributed any dedicated funds for MARTA’s operations, in 1966 Georgia voters approved a constitutional amendment to permit the state to fund 10 percent of the total cost of a rapid rail system in Atlanta. Two years later, in 1968, voters in Atlanta and MARTA’s core counties rejected a plan to finance MARTA through property taxes. In 1971—when the issue was presented to voters again—Clayton and Gwinnett voters dropped their support, and MARTA ended up being backed by only DeKalb, Fulton, and the City of Atlanta.

The compromise in 1971, that we finally got state legislators to agree on, was that MARTA would never be able to spend more than 50 percent of its sales revenue on operating costs, meaning it could never improve infrastructure and expand without finding money elsewhere--namely, in raising the fares and going into a lot of debt. The Atlanta Magazine article goes into the background and explains it all phenomenally. Please read it. There is a lot of politics involved. Basically, this compromise came out of state legislators bullying the city leaders into this, threatening that this whole thing would be dead on arrival, never happen at all, if they did not agree to this condition.

As an aside, this agreement doesn't even make clear sense to me. I mean, I don't see how this limit benefits anyone at all; it looks to only have been a mechanism with which to threaten, bully, and corner Atlanta leaders and lawmakers, a way to say, we'll do what we want and you, Atlanta, you'll have no say in this matter. Stop trying to be the big man on campus in this state. The problem is, Atlanta is the big man, and its potential--economic and social and otherwise--is probably permanently stunted as a result of the state's behavior towards it.

Am I being too harsh? Oh, I'm not done yet.

We had a couple of problems back in the 1960s and '70s. First, we loved the automobile, we were in the middle of a long-term love affair with our guzzling mobiles. Also, white people flocking to the suburbs really, really wanted to remain, steadfastly, separate from the city. That was precisely why they were leaving. Give me my oasis of picket fences, far away from that old wooden ship, diversity. I mean, yuck, right? But as the city has grown and become more diverse, and race relations have improved many degrees from the era of desegregation, the suburbs are also enclaves of multicultural communities. And now, none of us have any other way of getting from the suburbs to the city besides our cars. As the article succinctly and sardonically points out:

"This is the irony: The majority of whites in Atlanta wanted to be isolated when they thought about public transportation," says historian Kevin Kruse (who wrote this great book on white flight and Atlanta). "As a result, they have been in their cars on [interstates] 75 and 85. They got what they wanted. They are safe in their own space. Their just not moving anywhere."

YES!

The 1960 Census counted approximately 300,000 white residents in Atlanta. From 1960 to 1980, around 160,000 whites left the city--Atlanta's white population was cut in half over two decades, says Kruse [a Princeton professor]. Kruse notes that skeptics suggested Atlanta's slogan should have been "The City Too Busy Moving To Hate." [Atlanta touted itself for much of the 20th century as the City Too Busy To Hate.] "Racial concerns trumped everything else," Kruse says. "The more you think about it, Atlanta's transportation system was designed as much to keep people apart as to bring people together."

In the early 1970s, Morehouse College professor Abraham David observed, "The real problem is that whites have created a transportation problem for themselves by moving farther away from the central city rather than living in an integrated neighborhood."

Also, we could not help ourselves from building enormous highways, bingeing on federal grants to help us build them

The alluring of roaring around Atlanta in cool cars took over and never let go. Once MARTA was up and running, who would ride a bus or subway when they could drive a sleek, powerful car and ill it with cheap gas? Only the people who couldn't afford the car. MARTA became an isolated castaway, used primarily by poor and working class blacks.

...

David Goldberg, a former transportation reporter for the Atlanta Journal Constitution, says the road-building binge that lead to the gigantic highways that course through metro Atlanta--some of the widest in the world--diminished MARTA's potential. "It's not a single mistake but a bunch of decisions that add up to one mistake -- the failure to capitalize on the incredible success we had in winning funding for MARTA by undermining it with the incredible success we had in getting funding for the interstate highways," says Goldberg, now communications director for the Washington-based Transportation for America. "We were too damn successful--it was an embarrassment of success. Like a lot of of nouveau riche, we blew it before we knew what to do with it."

...

The vast highway system sucked up billions of federal dollars while the state refused to put a penny into MARTA--until the past fifteen years, during which it helped buy some buses. "The sick joke of it all is that we built the place to be auto-oriented and designed it about as bad as we could to function for auto use," Goldberg says. "The highway network we did build was designed in a way almost guaranteed to produce congestion--the land use around all that development put the nail in the coffin." He refers to neighborhoods full of cul-de-sacs that force cars onto crowded arterial roads lined with commercial activity, which eventually funnel down to one highway through the heart of Atlanta.

I feel strongly that what we delivered to ourselves on July 31 was at least fifty more years of the troubles that have plagued us for the last fifty. This time it might not be race that's guiding our decision; this time maybe it was economic recession, I don't know. But I agree, once again, with the assessment of Christopher B. Leinberger, a senior fellow of the Brookings Institute and a source for this same article:

The July 31 vote is "an Olympic moment" [here meaning, one of those seminal, deciding moments, like when we were awarded the honor of hosting the Olympics 1996 Games]. "If the vote fails, you have to accept the fact that Atlanta will continue to decline as a metro area."

Harsh, and probably true. I really, really hope not. I am invested in this city, and I love it. And I hate to see its future decided by the disagreements of the counties that compose its metro area. But I can't understand how this is not of the utmost importance in the state senate--this is, after all, the future of the biggest economic center in our state, and one of the biggest and most important in the southeast region. This is a big deal. I am inclined to blame the same idiotic political issues that have plagued the city folk versus the rural folk for a century in Georgia. Let's not have them define a second century, please.