Stirring up old leaves, long settled: Willie McGee, family history, and good storytelling

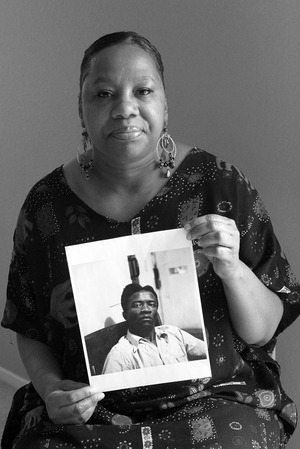

Last Friday, while waiting to depart for Charleston, S.C. to visit my brother, I was listening to All Things Considered. Nothing too unusual for five o'clock on a weekday, until I heard Bridgette McGee-Robinson's story, of an enduring curiosity and quest for answers regarding her grandfather, Willie McGee. In 1951, in the small town of Laurel, Mississippi, Willie McGee was charged with rape of a white woman and sentenced to the electric chair; his granddaughter's probing search for answers and emotions from the people who are still connected to that town and that case lead to one of the most touching pieces of radio storytelling that I've ever heard.

As with any such dive into a family's past, the descendants stir up dust that has oftentimes been more than happy to settle, and which is usually covering up a few things as well. As Ms. McGee-Robinson learns, it is a messy business bringing up what went down in small-town Mississippi between a black man and a white woman: she reports how the white folk in town knew it to be rape, while the black fold mostly agreed the alleged victim had been involved with Willie. (The alleged rape took place on a Friday morning, in the woman's bed, in the home she shared with her husband and young child.) Obviously the "family historian," as she calls herself at one point, while chatting with a Laurel local, is going to carry her own bias, and she may always see her grandfather as the saint (or the martyr) in the story; and it is important to keep in mind the social statuses and conditions of the people she is interviewing--both then and now. Even more vital is the relative impact sixty years can have on the details of each side of the story, and on the memories of those who lived through it, and those who heard the story passed down through there respective families.

As with any such dive into a family's past, the descendants stir up dust that has oftentimes been more than happy to settle, and which is usually covering up a few things as well. As Ms. McGee-Robinson learns, it is a messy business bringing up what went down in small-town Mississippi between a black man and a white woman: she reports how the white folk in town knew it to be rape, while the black fold mostly agreed the alleged victim had been involved with Willie. (The alleged rape took place on a Friday morning, in the woman's bed, in the home she shared with her husband and young child.) Obviously the "family historian," as she calls herself at one point, while chatting with a Laurel local, is going to carry her own bias, and she may always see her grandfather as the saint (or the martyr) in the story; and it is important to keep in mind the social statuses and conditions of the people she is interviewing--both then and now. Even more vital is the relative impact sixty years can have on the details of each side of the story, and on the memories of those who lived through it, and those who heard the story passed down through there respective families.

Ms. McGee-Robinson has by no means proven any new facts beyond all doubt. But as she reports, that was not her intention. What lied within this journey of discovery for her was a means through which to better understand what happened to her grandfather, and how best to see him in her own eyes. Ancestry is obviously important to each family in its own way, and comes with its own asteriskses and exceptions, oddities and inaccuracies, emotions and upsets. And at then end of the day, there will never be a definitive hard-fact truth to the matter, nor, usually, will any families receive the historical recognition they feel their ancestors are due. But stories like Willie McGee's, told through the eyes of his granddaughter, take this beef out of the equation entirely. It becomes much more than a little research on the lives contained in one family tree; it touches on the living memory of a city and on the racial flares that still erupt when we question a white woman and a black man romantically involved in the 1950s American South. It suddenly makes family histories, or at least this one, seem much more relevant than they had before to the larger historical narrative, and in a very good way. In a sense, it validates the arguments made for studying ancestry, while also explicitly pointing to the inevitable discrepancies and distortions of time and memory.

By the end of this radio segment, I was in tears; I couldn't believe the power this poignant story, and its development, had on me on that Friday afternoon, while I was set and ready to take to the road. As someone who has spent time preparing both historical and journalistic writing, I appreciate all the more the utterly nuanced elevation the piece contained, building until there was no way to turn it off; when you're writing for an audience, a story like the one she has is both coveted and exceedingly rare.

Listen to the entire radio diary here; it is worth the 23-minute investment, I promise. I would not dub this one of the most powerful things I've ever heard if I was not serious.