Year 1: babies illustrating humanity and, of course, themselves

The Babies didn't need many words; but I do. Anyone who knows me could diagnose the documentary film Babies (Bébés, Focus Features, 2010) as a Jessie-must-see: four babies from four different countries and cultures spend their first year in front of a camera, illustrating what is similar and what is different about their simultaneous childhoods. The moment I saw the Mongolian infant sitting in a water basin while a cow poked its head in to investigate, I was sold. And the whole layered story, which ultimately tells one story--that of the first year of life--is told without dialogue or narration; the babies speak for themselves with their expressions, exclamations, cries, and babble.

The Babies didn't need many words; but I do. Anyone who knows me could diagnose the documentary film Babies (Bébés, Focus Features, 2010) as a Jessie-must-see: four babies from four different countries and cultures spend their first year in front of a camera, illustrating what is similar and what is different about their simultaneous childhoods. The moment I saw the Mongolian infant sitting in a water basin while a cow poked its head in to investigate, I was sold. And the whole layered story, which ultimately tells one story--that of the first year of life--is told without dialogue or narration; the babies speak for themselves with their expressions, exclamations, cries, and babble.

This lack of adult voice immediately makes the story a universal human tale, removing language entirely and making it a tale of existence and survival, learning and growing. The things these babies are seeing for the first time were once seen by each of us for the first time as well. And the film makes that point again with its lack of dialogue, because babies don't use explanations or chatter to experience this wondrous place; what random conversations can be heard go over your head anyway, unless you speak all four of the languages surrounding these tiny children, so the story becomes even more about the babies, not the adults who have brought them here.

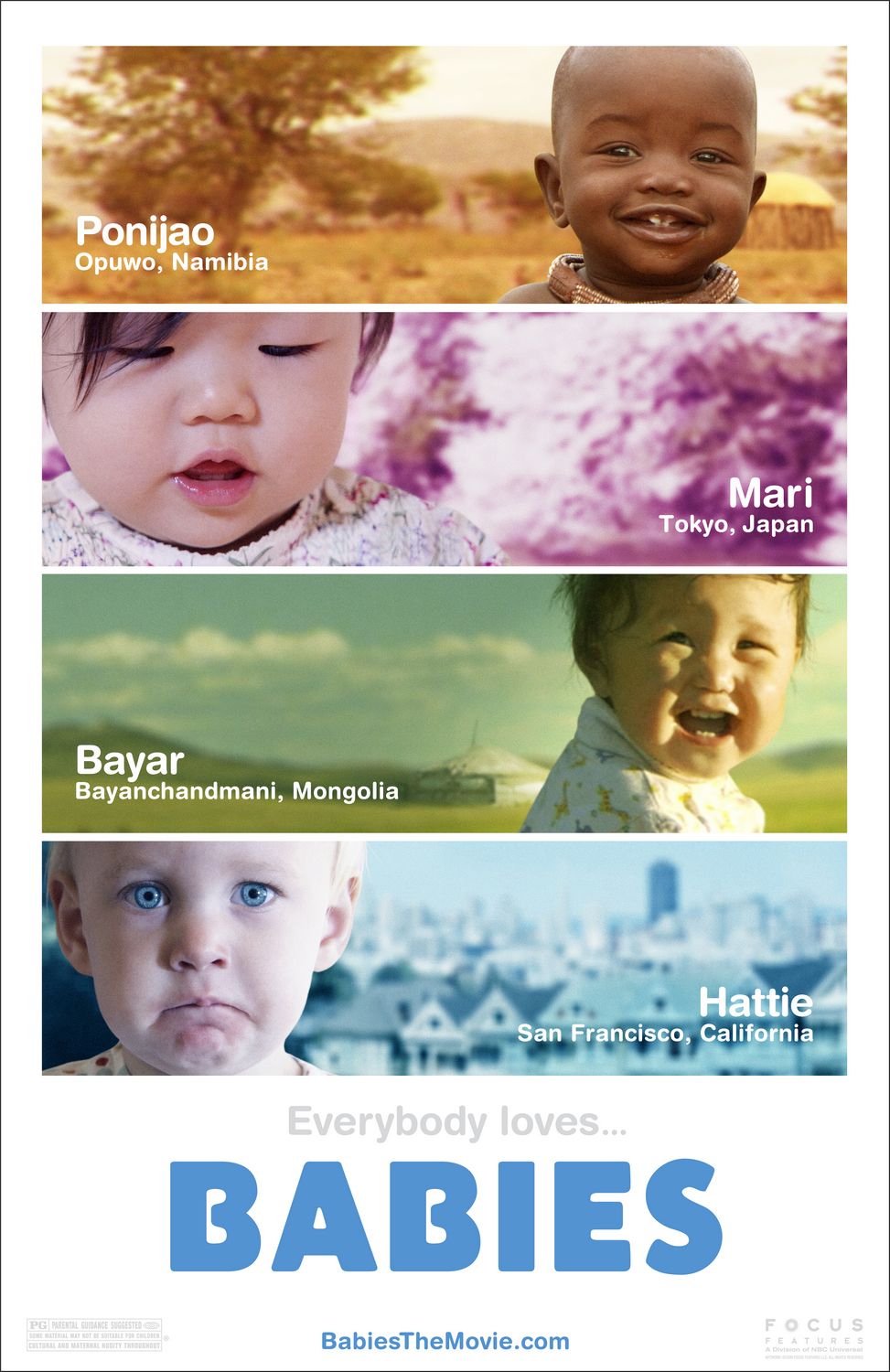

Ponijao lives in rural Namibia. Bayar lives in pastoral Mongolia. Hattie lives in free-spirited San Francisco, California. Mari lives in bustling Tokyo, Japan. Ponijao is not born in a hospital, while the latter three are. Ponijao also toddles around in a loin-cloth-like outfit, in direct contrast to Hattie, who wears a onesie; Ponijao regularly encounters flies and her head is dusted and smoothed with a coppery pigment, while Hattie rolls on the floor with the vacuum cleaner and encounters the lint roller first-hand. Hattie and Mari go to the doctor regularly; Bayar goes less frequently and Ponijao never does. The experiences of each child echoes the society into which they were born, illustrating the vivid contrasts in lifestyles worldwide.

Ponijao lives in rural Namibia. Bayar lives in pastoral Mongolia. Hattie lives in free-spirited San Francisco, California. Mari lives in bustling Tokyo, Japan. Ponijao is not born in a hospital, while the latter three are. Ponijao also toddles around in a loin-cloth-like outfit, in direct contrast to Hattie, who wears a onesie; Ponijao regularly encounters flies and her head is dusted and smoothed with a coppery pigment, while Hattie rolls on the floor with the vacuum cleaner and encounters the lint roller first-hand. Hattie and Mari go to the doctor regularly; Bayar goes less frequently and Ponijao never does. The experiences of each child echoes the society into which they were born, illustrating the vivid contrasts in lifestyles worldwide.

But within this is the more significant point: the variation in location and custom does not change the essential experience of these four babies. Each one eats, poops, bathes, laughs, cries. Each one discovers the feeling of water. Each one bonds with his parents. Bayar and Ponijao bond with their older siblings just the same way I bonded with my younger ones. Ponijao plays with stones, puts them in her mouth. Bayar wanders around with baby goats. Bayar, Mari, and Hattie all play with their pet cats, in a particularly charming series of scenes. As a very young infant, Bayar meets a rooster, who jumps right up on the cot with him; Bayar's eyes are wide with the glow of seeing something enchanting for the first time. Mari is driven through the insane consumerism of the developed world in her stroller, and we watch her take it all in. As all four start moving--crawling, standing, falling, walking--we share their wonder as they push further, watching their worlds expand. Hattie seems to intuit how to eat a banana, carefully peeling each section of the peel away and handing them off to her dad. Panijao has a knack for dancing, to the delight of her mother.

The romp through human life, year one, reminds the older audience of the sheer amount of things there are to absorb in this world, and how, for the most part, these things do not depend much on where you live, or whether your family lives in a hut, an apartment, or a house. There are animals; there is grass; there is music, and fruit, and older brothers. There are grandmothers' fingers, and buckets of water, and Legos--whether made of plastic or stone. And yes, there are mothers. We watch the babies struggle to get their point across with no words to use towards expressing it. This is the life of a baby, regardless of space or time. The differentiation between Ponijao, Mari, Bayar, and Hattie allows us to revel in diversity and appreciate the many ways motherhood and childhood are experienced around the world, but it also reminds us that there are certain essential parts of being human--and that babies can still survive, and thrive, without home nurseries, SUVs, and antibacterial hand sanitizer.